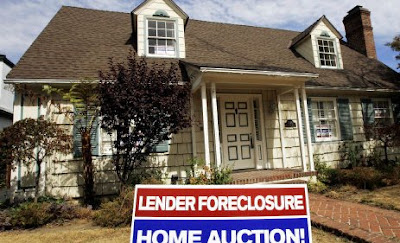

In an article over at MSN Money, Rick Newman of U.S. News World and Report talks about the looming recession and the sub-prime loan mess that we’re finding ourselves stuck in.

With 2 million home foreclosures possible over the next two years and the economy stumbling toward recession, it’s clear that Washington will enact new reforms meant to curtail reckless lending, attach big-print disclaimers to risky securities and prevent any more self-triggered implosions in the financial markets.

The Federal Reserve has already engineered one Wall Street bailout, something it may have to do again. Congress, the Treasury Department and other regulators are proposing dozens of new rules.

Some of them might work.

But we’re not at the end of the housing crash or the economic downturn — we’re still in the middle, where vision is much worse than 20/20. That means politicians and regulators could end up imposing solutions before they even fully understand the problem.

Rick goes on to list some of the misconceptions that a lot of people have about this whole fiasco:

- Subprime loans are inherently bad. The fundamental problem isn’t the foreclosure rate; it’s that the loans have been priced too low. The interest rates and upfront costs imposed on borrowers haven’t been high enough to cover the overall risks of default. “Congress should not aim for foreclosure rates of zero,” says James Barth, an economist with the nonprofit Milken Institute. “It’s OK to have risky loans, but the rates have to be higher.”

- Low interest rates are always good. If you’re buying a house, you want a mortgage rate that’s as low as possible. But low rates aren’t necessarily the best thing for the overall economy. Economists often warn about “overheating,” a dangerous byproduct of low rates Interest rates fell significantly between 2000 and 2004, largely because the Federal Reserve repeatedly cut its own short-term lending rates. That generated economic phenomena with long-term consequences. One was increased demand for assets like houses — because the money to buy them was cheap and plentiful — which in turn caused prices to rise at a pace that turned out to be unsustainable.

Then, as rates on conventional securities, such as Treasury bills, fell to paltry levels, investors began to demand new kinds of securities with higher returns. Subprime loans, bundled into complex mortgage-backed securities, fit the bill, and lenders began to solicit as many of them as they could find. No worries; the computers assured that the risk was perfectly manageable.

We’re now paying a price for those years of cheap money, in the form of a burst housing bubble and a staggering economy. John Chapman of the American Enterprise Institute predicts “an era of unpleasant choices” characterized by widespread bankruptcies, layoffs and a longer recession than necessary.

- A massive taxpayer “bailout” is under way.When the Fed brokered the buyout of Bear Stearns by JPMorgan Chase , it took responsibility for $29 billion of troubled securities, money that will indeed come out of taxpayers’ pockets if the whole portfolio turns out to be worthless. But the Fed eventually will sell the securities for something — and perhaps recoup most or all of the money it has pledged.

- Buyers are well-informed and rational. Investment vehicles might be remarkably innovative, but consumers seem to be as gullible as ever.

It’s obvious now that some home buyers over the past few years took out loans far beyond what they could afford, with foreclosure probably inevitable even if house prices had continued to rise. But even people who consider themselves financially literate aren’t so shrewd. A 2007 study by the Federal Trade Commission, for instance, instance, found that:

* 20% of borrowers looking at mortgage disclosure forms couldn’t identify the interest rate amount.

* 24% couldn’t tell which loan was less expensive, when looking at two different applications.

* 30% couldn’t tell if the loan included an expanded “balloon payment” at some point.

* 44% couldn’t tell if there was a prepayment penalty for refinancing within two years.

Subprime borrowers aren’t the only dupes. Prime borrowers fared only slightly better on most of the questions.

I think the market is just correcting itself right now, and it had to happen sooner or later given the bad lending and borrowing practices so many people were getting themselves into. What do you think?

While we’re on the subject of foreclosure, here’s a great post about what your bank wants to hear when you go into foreclosure.

LINKS:

Subprime myths: What Washington gets wrong

Share Your Thoughts: